The statistics in this table are Official Statistics. Source: Home Office Operational Statistics Data Collection, figures supplied by fire and rescue authorities.

Contact: FireStatistics@homeoffice.gsi.gov.uk

Next Update: Autumn 2017

The full set of fire statistics releases, tables and guidance can be found on our landing page, here-

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/fire-statistics

Financial Years

2015/16 refers to the financial year, from 1st April 2015 to 31 March 2016. Other years follow the same pattern.

Note on 2009/10:

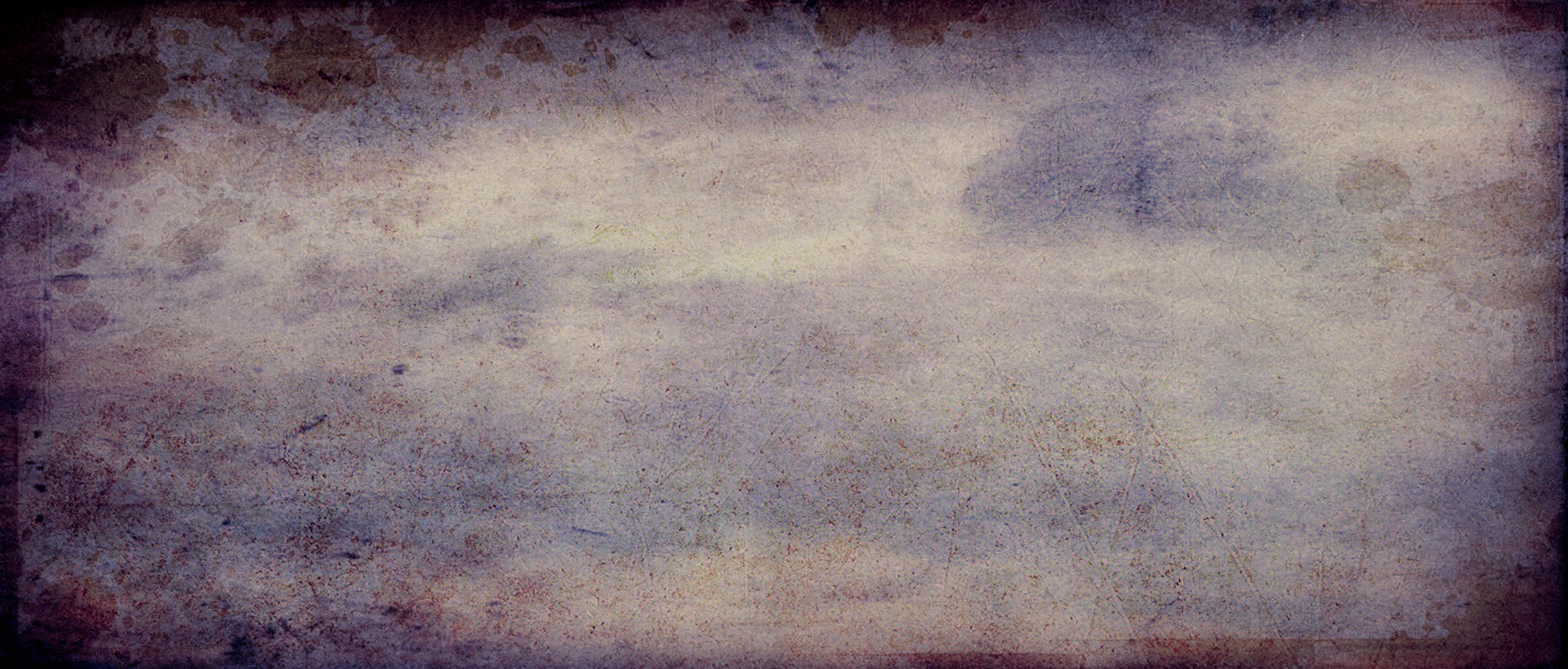

Before 1 April 2009 fire incident statistics were based on the FDR1 paper form. This approach means the statistics for before this date can be less robust, especially for non-fire incidents which were based on a sample of returns. Since this date the statistics are based on an online collection tool, the Incident Recording System (IRS).

General note:

Fire data are collected by the IRS which collects information on all incidents attended by fire services. For a variety of reasons some records take longer than others for fire services to upload to the IRS and therefore incident totals are constantly being increased (by relatively small numbers). This is why the differing dates that data are received by is noted above.

Note on Imputed figures

During 2009/10, Greater Manchester and Hertfordshire Fire and Rescue Services were unable to fully supply their casualty data. As such totals for these Fire and Rescue Services were imputed. For these imputed records detailed breakdowns are not available. As such, some detailed breakdowns may not sum to their corresponding totals.

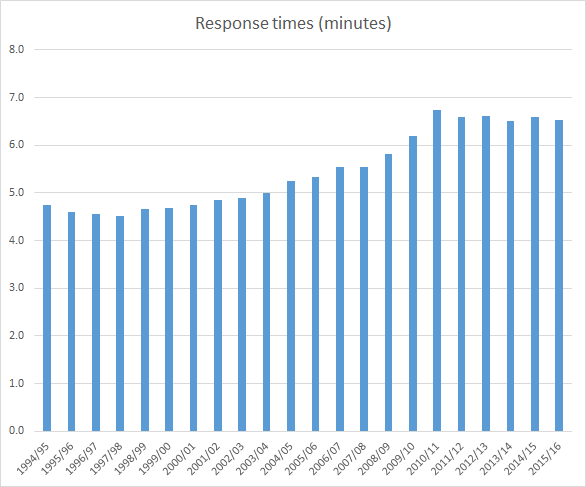

The England total hours figures above for "Number of Fire Risk Checks carried out by FRS" include imputed figures to ensure a robust national figure. These imputed figures are-

2015-16: Staffordshire

2014-15: Staffordshire, Surrey

2013-14: Cleveland, Staffordshire, Surrey

2012-13: Cleveland, Staffordshire, Surrey

2011-12: Cleveland, Lincolnshire

2011-12: Bedfordshire, Cleveland, Greater London

Figures for "Fire Risk Checks carried out by Elderly (65+)", "Fire Risk Checks carried out by Disabled" and "Number of Fire Risk Checks carried out by Partners" do not include imputed figures because a large number of fire authorities are unable to supply these figures.

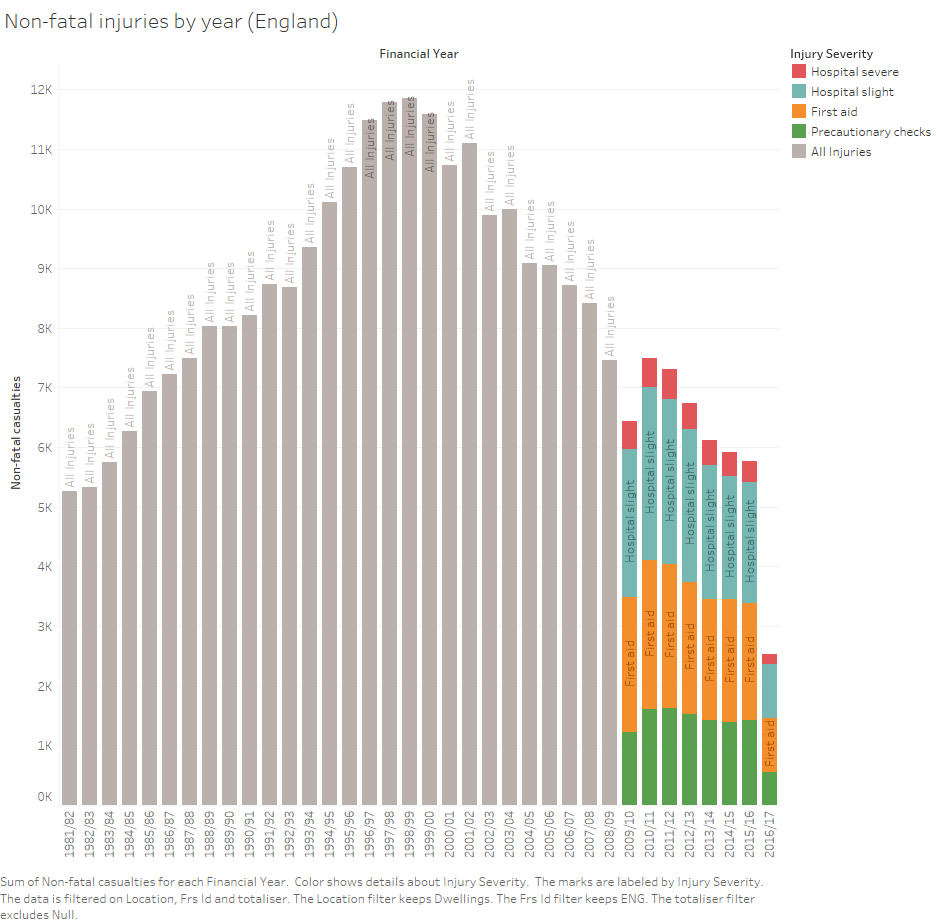

1 Some fires are excluded when calculating average response times. Please see definition document for a more detailed explanation.

2 Primary fires are those where one or more of the following apply: i) all fires in buildings outdoor structures and vehicles that are not derelict, ii) any fires involving casualties or rescues, iii) any fire attended by five or more appliances

3 The largest components of 'other buildings fires' are incidents in private garden sheds, retail and food/drink buildings

4 Typically outdoor fires that are ‘primary’ because of a casualty or casualties, or attendance by five or more appliances5 Typically outdoor fires not involving property

Definitions

1 Primary fires are defined as fires that meet at least one of the following conditions:

(a) any fire that occurred in a (non-derelict) building, vehicle or outdoor structure,

(b) any fire involving fatalities, casualties or rescues,

(c) any fire attended by five or more pumping appliances.

2 Includes fatalities marked as "fire-related" but excludes fatalities marked as "not fire-related". Those where the role of fire in the fatality was "not known" are included in "fire-related". Fire-related deaths are those that would not have otherwise occurred had there not been a fire. i.e. ‘no fire = no death’.

3 Dwellings includes HMOs, Self contained Sheltered Housing, Caravans/mobile homes, Houseboats, Stately Homes and Castles (not open to the public).

4 If more than one smoke alarm was recorded for a fire, the fire is categorised under the most positive operation status of all the smoke alarms recorded.

The data in this table are consistent with records that reached the IRS by 4th January 2017.

1 Accidental is defined as when the motive for the fire was recorded as either Accidental or Not known. As such this excludes deliberate fires.

2 Other breathing difficulties includes: Choking and Other breathing difficulties.

3 Physical injuries includes: Back/neck injury (spinal), Bruising, Chest/abdominal injury, Concussion, Cuts/lacerations, Fracture, Head injury, Impalement and Other physical injuries.

4 Other includes: Collapse, Drowning, Heat exhaustion, Hypothermia, Other and Unconscious.